Did YOU know the USA has a Federal Data Strategy? Or that it’s part of National US Plan for Open Government? This President and White House should have told you, instead of failing to engage Americans. I participated in another … Continue reading

Did YOU know the USA has a Federal Data Strategy? Or that it’s part of National US Plan for Open Government? This President and White House should have told you, instead of failing to engage Americans. I participated in another … Continue reading

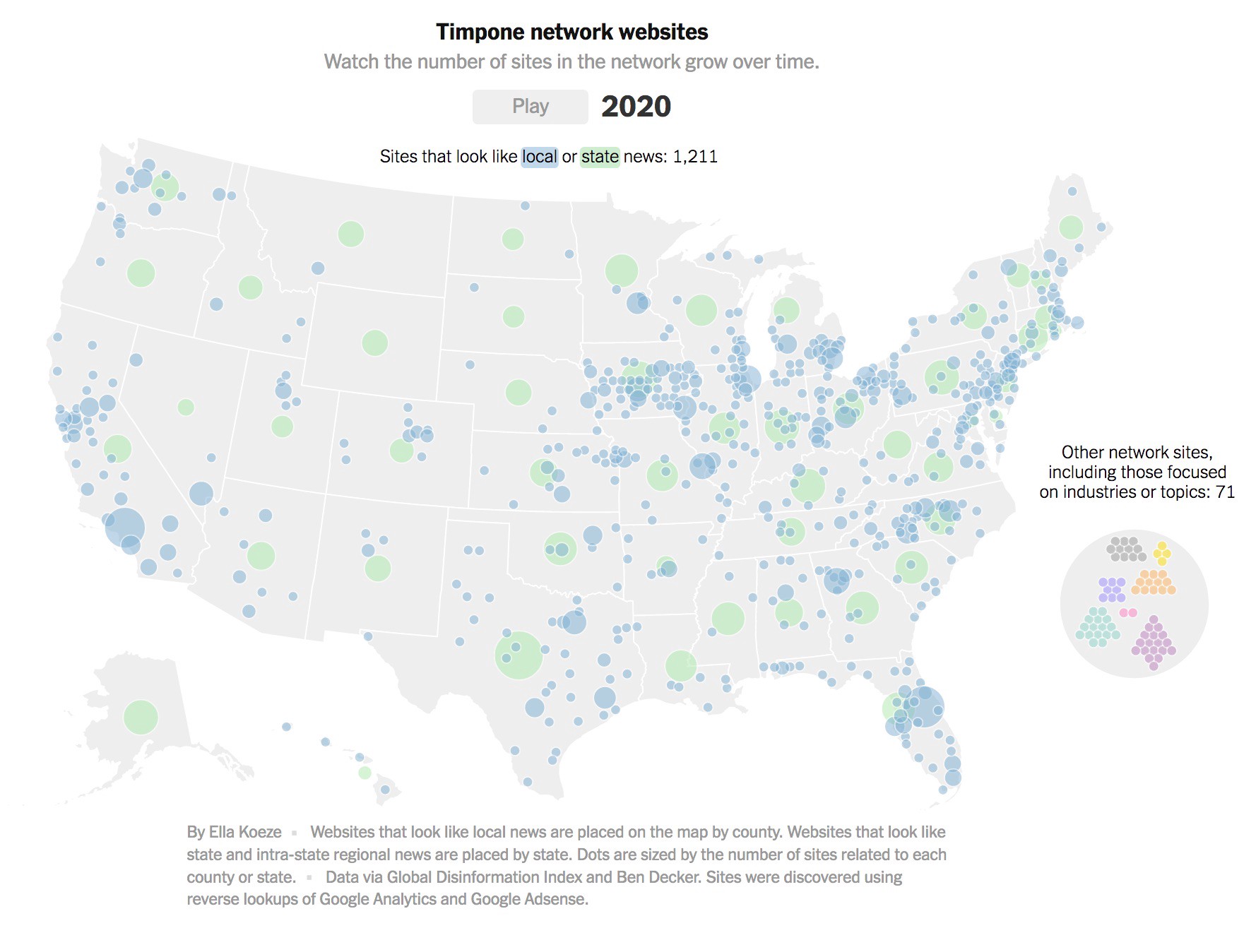

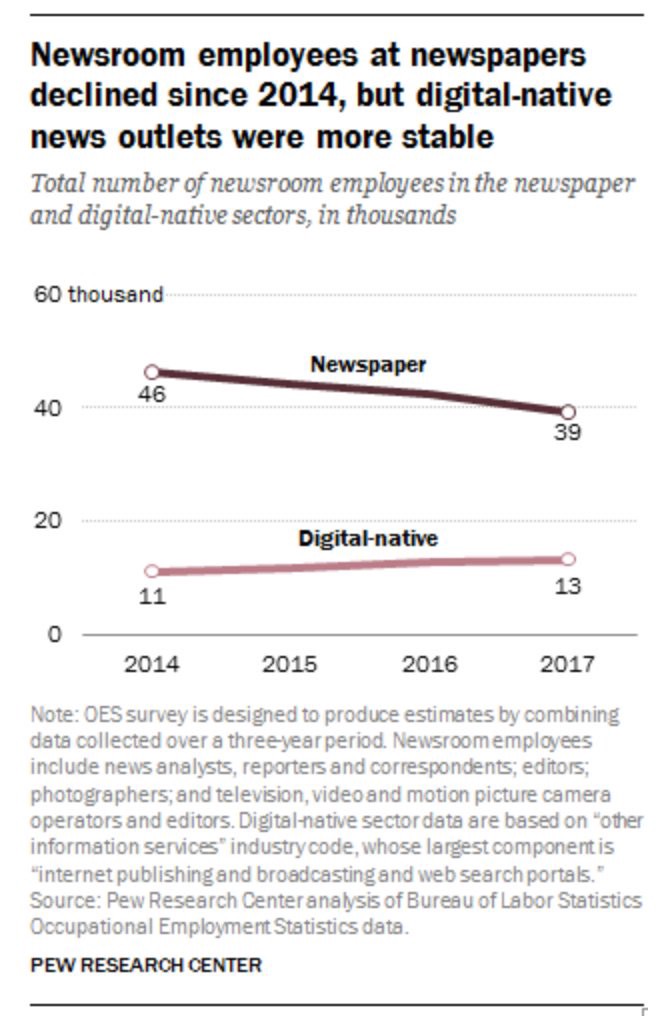

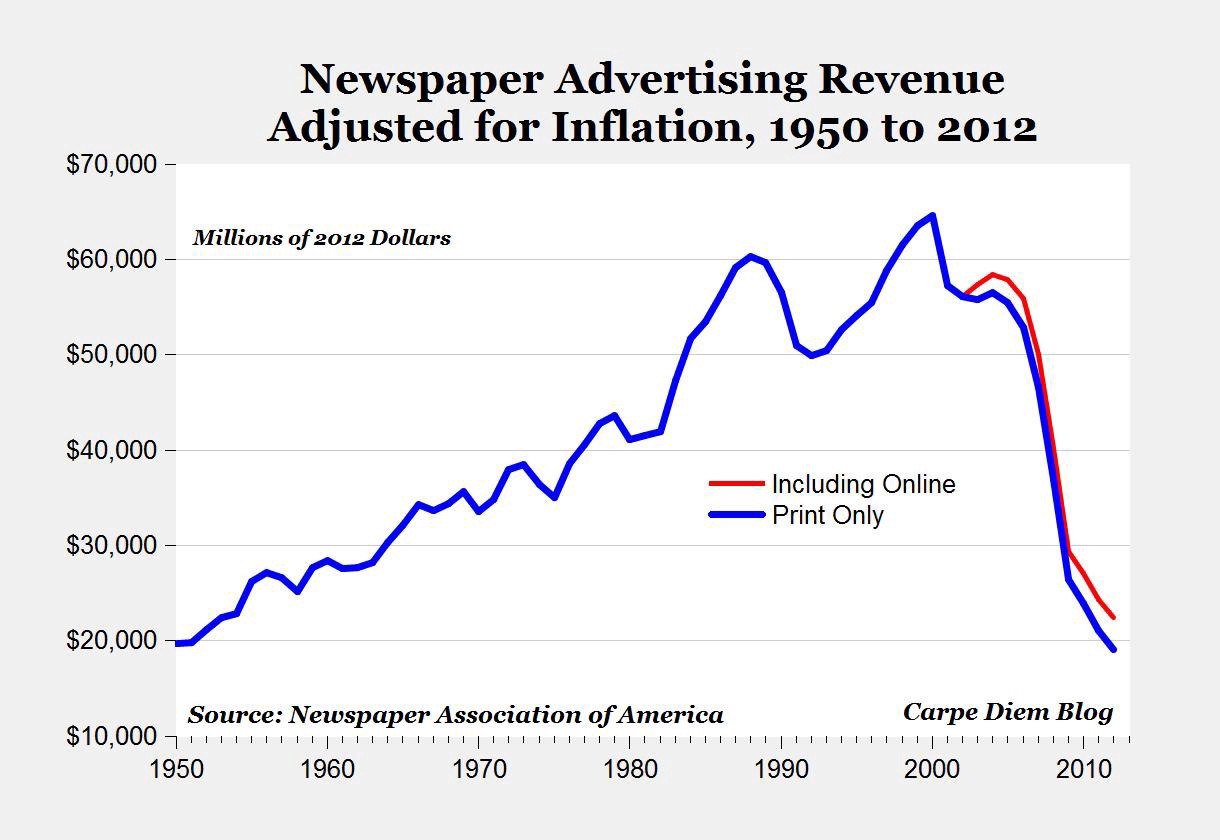

In the same way that poor diets affect our physical health, America’s infodemic is being fueled by poor information diets. About 2,100 newspapers have folded since 2004, driving a ~58% decline in newsroom employment.

Digital outlets have not replaced the jobs or journalism reporters produced and editors verified.

Now, the New York Times reports that “pink slime” outlets are filling the information voids left behind, with the emergence of pay-for-play digital outlets that launder partisan attacks for a few dollars an article and digital duopoly of Facebook and Google dominates the digital advertising markets.

None of this is new nor, in 2020, can we really say that no one saw this coming.

Clay Shirky was brutally honest about the fate of the newspapers back in 2014, after he “thought about the unthinkable” in 2009.

In an essay that accurately predicted the ongoing trend in the industry, Shirky asked the crucial question that keeps people who believe democracies depend on a robust, independent free press to inform publics engaging in self-governance: “who covers all that news if some significant fraction of the currently employed newspaper people lose their jobs?”

His answer remains instructive:

Society doesn’t need newspapers. What we need is journalism. For a century, the imperatives to strengthen journalism and to strengthen newspapers have been so tightly wound as to be indistinguishable. That’s been a fine accident to have, but when that accident stops, as it is stopping before our eyes, we’re going to need lots of other ways to strengthen journalism instead.

When we shift our attention from ’save newspapers’ to ’save society’, the imperative changes from ‘preserve the current institutions’ to ‘do whatever works.’ And what works today isn’t the same as what used to work.

We don’t know who the Aldus Manutius of the current age is. It could be Craig Newmark, or Caterina Fake. It could be Martin Nisenholtz, or Emily Bell. It could be some 19 year old kid few of us have heard of, working on something we won’t recognize as vital until a decade hence. Any experiment, though, designed to provide new models for journalism is going to be an improvement over hiding from the real, especially in a year when, for many papers, the unthinkable future is already in the past.

For the next few decades, journalism will be made up of overlapping special cases. Many of these models will rely on amateurs as researchers and writers. Many of these models will rely on sponsorship or grants or endowments instead of revenues. Many of these models will rely on excitable 14 year olds distributing the results. Many of these models will fail. No one experiment is going to replace what we are now losing with the demise of news on paper, but over time, the collection of new experiments that do work might give us the reporting we need.

There were good ideas in the Knight Commission’s report on the information needs of American democracy, but it’s hard for me to argue that the polluted social media and cable news ecosystems of today are meeting them, given the collapse documented above.

In 2020, there is still no national strategy to catalyze that journalism, despite the clear and present danger absence poses to the capacity of the American people to engage in self-governance or the shared public facts necessary for effective collective action in response to a public health threat.

Investors, philanthropists, foundations, and billionaries who care about the future of our nation needs to keep investing in experiments that rebuild trust in journalism by reporting with the communities reporters cover using the affordances of social media, not on them.

Publishers could build out new forms of service journalism based upon data that improve access to information, empower consumers, patients, and constituents to make better choices, and ask the people formerly known as the audience to help journalists investigate.

We need to find more sustainable business models that produce investigative journalism that don’t depend on grants from foundations and public broadcasting corporations, though those funds will continue be part of the revenue mix.

As Shirky said, “nothing will work, but everything might. Now is the time for experiments, lots and lots of experiments, each of which will seem as minor at launch as craigslist did, as Wikipedia did, as octavo volumes did.”

Finally, state governments need to subsidize public access to publications and the Internet through libraries, schools, and wireless networks, aiming to deploy gigabit speeds to every home through whatever combination of technologies gets the job done.

The FCC, states and cities should invest in restorative information justice. How can a national government that spend hundreds of billions on weapon systems somehow have failed to provide a laptop for each child and broadband Internet access to every home?

It is unconscionable that our governments have allowed existing social inequities to be widened in 2020, as children are left behind by remote learning, excluded from the access to the information, telehealth, unemployment benefits, and family that will help them and their families make it through this pandemic.

Information deprivation should not be any more acceptable in the politics of the world’s remaining hyperpower than poisoning children with lead through a city water supply.

Digital democracy reforms tends to advance or retreat in fits and starts, but when exigent circumstances require more from us and our governments, change can happen unexpectedly. On May 26, I requested an absentee ballot, intending to cast my vote … Continue reading

The United States needs a “whole of society” effort to increase resilience against disinformation and misinformation, particularly in the context of a global pandemic. Unfortunately, the actions of the Trump White House are weakening the health of our body politic, … Continue reading

The past decade has shown the world again and again how important anti-corruption watchdogs and nonpartisan advocates for transparency and accountability are for defending civil liberties and public access to information, online and off. The stress test that the Trump … Continue reading

When it comes to using location data to surveil the incidence and spread of the novel coronavirus, efficacy is what matters. Presidents, legislatures, and regulators around the world are trying to learn how to leverage existing and emerging technologies to … Continue reading

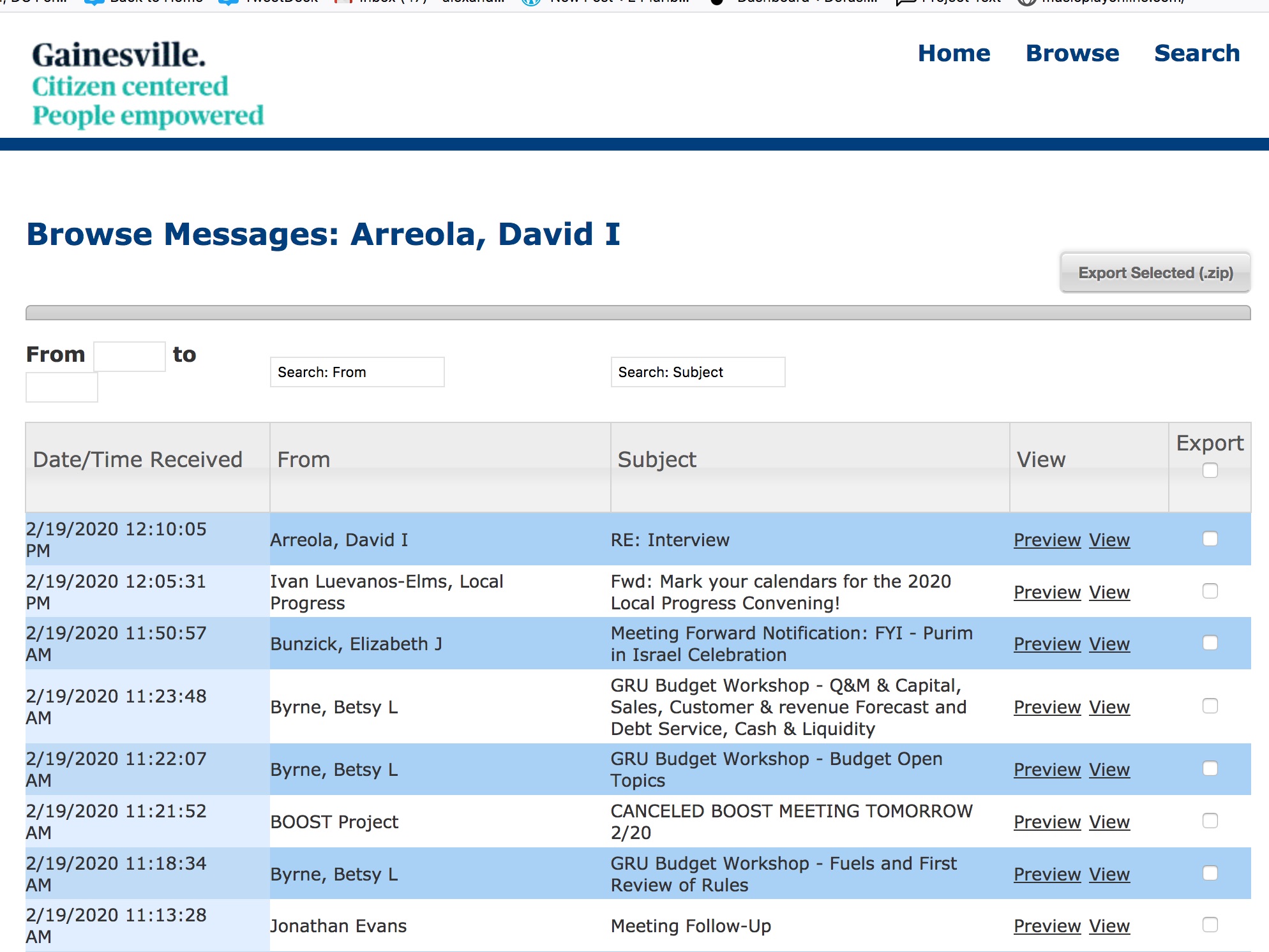

There’s much to be learned from the experience of the city Gainesville, Florida, where a commissioners voted in 2014 to publish the public’s email correspondence with them and the mayor online.

More than five years on, the city government and its residents have are ground zero for an tumultuous experiment in hyper-transparent government in the 21st century, as Brad Harper reports for the Montgomery Advertiser.

It’s hard not to read this story and immediately see a core flaw in the design of this digital governance system: the city government is violating the public’s expectation of privacy by publishing email online.

“Smart cities” will look foolish if they adopt hyper-transparent government without first ensuring the public they serve understands whether their interactions with city government will be records and published online.

Unexpected sunshine will also dissolve public trust if there’s a big gap between the public’s expectations of privacy and the radical transparency that comes from publishing the emails residents send to agencies online.

Residents should be offered multiple digital options for interacting with governments. In addition to exercising their rights to freedom of expression, assembly and petition on the phone, in written communications with a given government, or in person at hearing or town halls, city (and state) governments should break down three broad categories of inquiries into different channels:

Emergency Requests: Emergency calls go to 911 from all other channels. Calls to 911 are recorded but private by default. Calls should not be disclosed online without human review.

Service Requests: Non-emergency requests should go 311, through a city call center or through 311 system. Open data with 311 requests is public by default and are disclosed online in real-time.

Information Requests: People looking for information should be able to find a city website through a Web search or social media. A city.gov should use a /open page that includes open data, news, contact information for agencies and public information officers, and a virtual agent or “chat bot” to guide their search.

If proactive disclosures aren’t sufficient, then there should be way to make Freedom of Information Act requests under the law if the information people seek is not online. But public correspondence with agencies should be private by default.

FierceElectronics reports that Draganfly is claiming that their technologies can, when attached to a drone, detect fever, coughs, respiration, heart rate, & blood pressure for a given human at a distance. Put another way, this drone company is saying that … Continue reading

Informing the public during a pandemic has always been a challenge for public health officials, but the information landscape of 2020 has been polluted by the the Trump administration’s history of lying in ways that make response to the coronavirus much more difficult.

As University of California law professor David Kaye wrote this past weekend, “government disinformation about public health is itself a public health risk.”

Put bluntly: if publishers and producers don’t change how they report on Trump’s disinformation viruses, public health will be put at even more risk. Consider the messenger: Kaye, the current United Nations special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, is no friend of censorship or laws that curb speech. Instead, he’s asking politicians, pundits, the public and, most of all, journalists to be responsible about what we say or pass on in this crisis.

If spreading Trump’s disinformation damages public health, as it as with coronavirus, then officials, tech companies and media all face a common challenge in 2020: how to prevent harm by putting the lies of a President of the United States into epistemic quarantine, whether he bellows them from a bully pulpit at a rally or tweets them from the White House.

News organizations are a host for his disinformation viruses. (In the case of ideologically aligned networks, they are a willing one.) Partisans, the public, and bad actors spread them, too.

While we can and should try to inoculate publics with knowledge about influence campaigns, it’s hard to vaccinate someone against a disinformation virus in a polarized, low-trust media environment. It is especially hard when the sickness comes from inside of a White House.

Perversely, putting sunlight on disinformation may not “disinfect” it, but instead infect a far greater population through calling public attention to it.

Getting disinformation into wider discourse is precisely the goal of the people making intentionally misleading statements, otherwise known as lies, or “malinformation,” which is “information that is based on reality, used to inflict harm on a person, organization or country.”

We’re in novel territory, given the scale and velocity of modern communications across social media platforms and public access through connected devices, but we’ve been living through an increasingly toxic, polluted information ecosystem for enough years to undertsand and make adjustments.

Unfortunately, newsrooms still haven’t adjusted to the reality that folks “flooding the zone” with disinformation is a feature, not a bug, of this administration.

Remember, Steve Bannon, chairman of the Trump campaign and then White House advisor, said that “the real opposition is the media. And the way to deal with them is to flood the zone with shit.”

If your democracy is in an epistemic crisis, and viral disinformation poses an ongoing public health risk, then newsroom leaders need to change their practices.

Focusing on fighting viral disinformation as a public health issue, as opposed to information warfare, may be a useful frame.

For instance, while it’s publishing amazing journalism, the New York Times is still failing:

Dear @NYTimes editors: When you spread Trump’s lies in headlines & tweets, you are compromising your role as the immune system for democracy.

He’s playing you, @peterbakernyt.

Please inoculate the public against disinformation viruses. Don’t spread them. https://t.co/Q5buozm14m https://t.co/fNfsBwYjgb— Alex Howard (@digiphile) March 5, 2020

Editors need to change how they’re reporting on Trump, or he’ll keep hacking the standards and practices developed in the professionalization of “objective journalism” (we report what POTUS says/you decide) to infect the public with disinformation viruses. Try Lakoff’s approach:

Truth Sandwich:

1. Start with the truth. The first frame gets the advantage.

2. Indicate the lie. Avoid amplifying the specific language if possible.

3. Return to the truth. Always repeat truths more than lies.

Hear more in Ep 14 of FrameLab w/@gilduran76https://t.co/cQNOqgRk0w— George Lakoff (@GeorgeLakoff) December 1, 2018

Publishers, platforms and the public should deny lies the “oyxgen of amplification and put disinformation viruses in “epistemic quarantine.”

Derek Thompson describes this as “a combination of selective abstinence (being cautious about giving over headlines, tweets, and news segments to the president’s rhetoric, particularly when he’s spreading fictitious hate speech) and aggressive contextualization (consistently bracketing his direct quotes with the relevant truth).”

Television producers need to change too, particularly on broadcast and cable news shows. A Meet the Press special on disinformation this winter grappled with these issues, but ultimately fell far short of what was required to inform the public, warn us of the public health threat that Trumpian BS posed, and adjust its own editorial practices.

Watching the @MeetThePress special on disinformation.

They led with some greatest/worst hits:

“Alternative facts.”-@KellyannePolls

“Truth is not truth”-@rudygiuliani

“Just remember, what you are seeing and what you are reading is not what’s happening.”-@realDonaldTrumpLies? pic.twitter.com/m5NJB0rCE9

— Alex Howard (@digiphile) December 29, 2019

A President who spreads disinformation viruses during a pandemic is a wicked problem. Journalism professor Jay Rosen diagnosed the structural problem media outlets have years ago and listed approaches newsrooms could take:

Here is how the Los Angeles Times put it on July 14: “We shouldn’t rise to his bait, but how can we not? If we ignore him, we normalize his reckless behavior, and that’s even worse.” https://t.co/HeSEuvLcBR

Welcome to my new THREAD, where I try to solve this problem. 1/

— Jay Rosen (@jayrosen_nyu) July 21, 2019

News media should adopt and adapt Rosen’s ideas. Experiment. Share what they learn, and pool resources. But today, they should stop putting lies in headlines and chyrons.

If government disinformation about public health is itself a public health risk, then journalists must stop spreading it, now.

The stakes will only get higher if our nation is drawn into a war, misleads the public about a conflict, or starts one under false pretenses.

Yesterday, the United States Freedom of Information Act Advisory Committee met at the National Archives in Washington and approved a series of recommendations that would, if implemented, dramatically improve public access to public information. And in May, it will consider … Continue reading