In December 2021, President Biden urged “every nation in the Open Government Partnership to take up a call to action to fight the scourge of corruption, to “stand with those in civil society and courageous citizens around the world who are demanding transparency of their governments,” and to “all work together to hold governments accountable for the people they serve.”

Almost two years later, the United States is still not leading by the power of our example by including the priorities of US civil society organizations in additional commitments and engaging the American people and press using the bully pulpit of the White House, despite rejoining the Open Government Partnership’s Steering Committee.

That disconnect was evident at a public meeting with the Department of Justice’s Office of Information Policy (OIP) on September 26, 2023. Members of the public and press who are interested in a first look at the Freedom of Information “Wizard” the OIP has been building with Forum One Communications can watch recorded video of the meeting on YouTube, along with DoJ’s work on common business standards and the “self-assessment toolkit” the agency updated. All three of these pre-existing initiatives were submitted as commitments on FOIA in the 5th U.S. National Action Plan for Open Government last December.

The General Services Administration’s new Open Government Secretariat will post a “meeting record” at open.usa.gov — their summary of what happened — though it’s not online yet. (Slides are online, along with agenda and screenshots.)

We posed a number of questions via chat that Lindsey Steel from OIP acknowledged, though not always directly answered — like the U.S. government not co-creating any of the FOIA commitments that were being discussed with civil society, in the Open Government Partnership model. (Unlike other previous public meetings in 2022 and 2023, members of civil society were given the opportunity to ask questions on video.)

While it’s both useful and laudable for OIP to take public questions on its work, the pre-baked commitments they presented on were not responsive to the significant needs of a historic moment in which administration of the Freedom of Information Act appears broken to many close observers, and follow an opaque, flawed consultation that was conducted neither in the spirit nor co-creation standards of the Open Government Partnership itself.

While the Open Government Partnership’s Independent Review Mechanism is far slower that press cycles in 2023, the independent researchers there have caught up with the USA’s poor performance since 2016. (Unfortunately, the OGP’s Independent Review Mechanism and Steering Committee’s governance processes both move too slowly to sanction governments during or after the co-creation process for failing to meet co-creation standards in a way that would have empowered US civil society in 2022.)

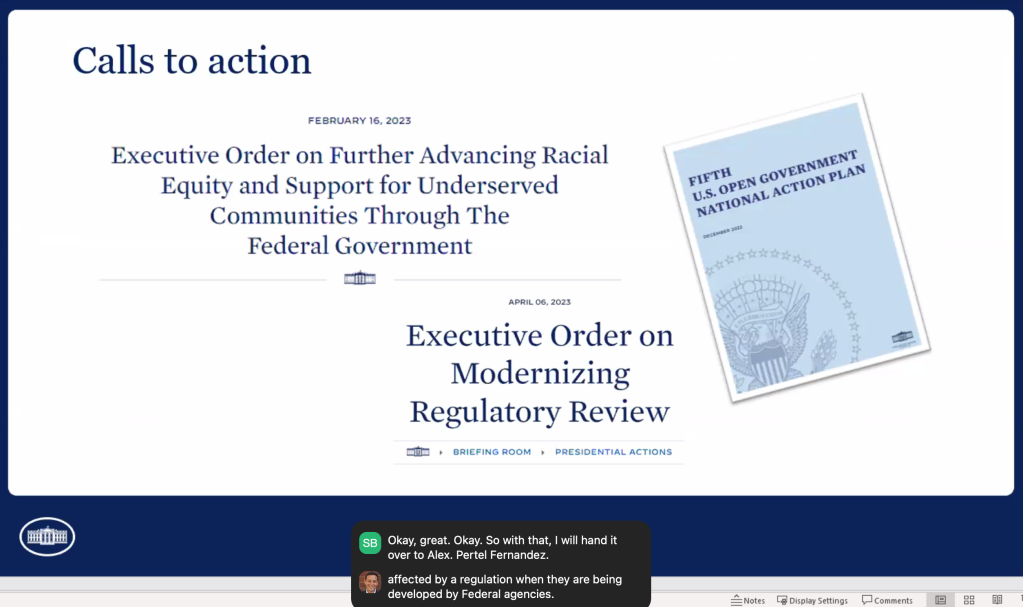

In a letter dated August 13, 2023, the Open Government Partnership formally informed the US government on August that it has acted contrary to process in its co-creation of.4th National Action Plan for Open Government and implementation of the plan.

The U.S. government’s response did not directly acknowledge any of the substantive criticism in the IRM or by good government watchdogs, much less announce a plan to address its failure to co-create a 5th National Action Plan last fall by coming back to the table.

Instead, the General Services Administration simply promised to do better in 2024 in a 6th plan and to keep updating the public on the work U.S. government was already doing.

The request of the coalition prior to the Open Government Partnership Summit was for the U.S. government to come back to the table and co-create new commitments that are representative of our priorities, not to continue hosting virtual webinars at which civil servants provide “updates” on pre-existing commitments in order to be in compliance with the bare minimum that OGP asks of participating nations.

With respect to FOIA, doing more than the minimum would look like the White House making new commitments to effective implementation of the FOIA Improvement Act of 2016 and the Open Government Data Act through executive actions, including:

- Building on U.S. Attorney General’s memorandum mandating the presumption of openness and ensure fair and effective FOIA administration.

- Convening the U.S. Digital Service, 18F, and the nation’s civic tech community to work on improving FOIA.gov, using the same human-centric design principles for improved experience that are being applied to service delivery across U.S. government.

- Making sure FOIA.gov users can search for records across reading rooms, Data.gov, USASpending.gov, and other federal data repositories.

- Restoring a Cross-Agency Priority goal for FOIA.

- Advising agencies to adopt the US FOIA Advisory Committee recommendations.

- Tracking agency spending on FOIA and increase funding to meet the demand.

- Directing the Department of Justice to roll out the “release-to-one, release-to-all” policy for FOIA piloted at the direction of President Obama, which the State Department has since adopted.

- Collecting and publishing data on which records are being purchased under the FOIA by commercial enterprises for non-oversight purposes, and determine whether that data can or should be proactively disclosed.

- Funding and building dedicated, secure online services for people to gain access to immigration records and veterans records — as the DHS Advisory Committee recommended — instead of forcing them to use the FOIA.

- Commiting to extending the FOIA to algorithms and revive Code.gov as a repository for public sector code.”

We continue to hope that President Biden will take much more ambitious actions on government transparency, accountability, participation, and collaboration in order to restore broken public trust in our federal government, acting as a bulwark against domestic corruption and authoritarianism.

On May 10, the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress in the United States House of Representatives held a hearing on “opening up the process,” at which 4 different experts talked with Congress about making legislative information more transparent,” from ongoing efforts to proposed reforms to the effect of sunshine laws passed decades ago.

On May 10, the Select Committee on the Modernization of Congress in the United States House of Representatives held a hearing on “opening up the process,” at which 4 different experts talked with Congress about making legislative information more transparent,” from ongoing efforts to proposed reforms to the effect of sunshine laws passed decades ago.